Byron Alfred Whitmarsh was born in Mocane Oklahoma, on April 18, 1923. After graduating from high school he enrolled in Civil Engineering at Oklahoma A & M in September 1942. This is where he got his first taste of the Army.

“…It was required at Oklahoma A & M that every able-bodied male should take ROTC for at least two years. The officer in charge of the Engineering ROTC unit convinced most of us students that it would be to our advantage to enlist in the Enlisted Reserve rather than waiting for the draft which was sure to get us anyway. I took the physical and enlisted in the reserve on October 9, 1942. We were activated May 11, 1943 and entered service at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma … After finishing basic I was sent to the ASTP Unit at Sam Houston College for Engineering Academic Basic. The program was stopped and we were sent to the 99th on March 4, 1944. When we went overseas in October, I was a rifleman in the 2nd Squad, 3rd Platoon, C Company, 395th Regiment …”

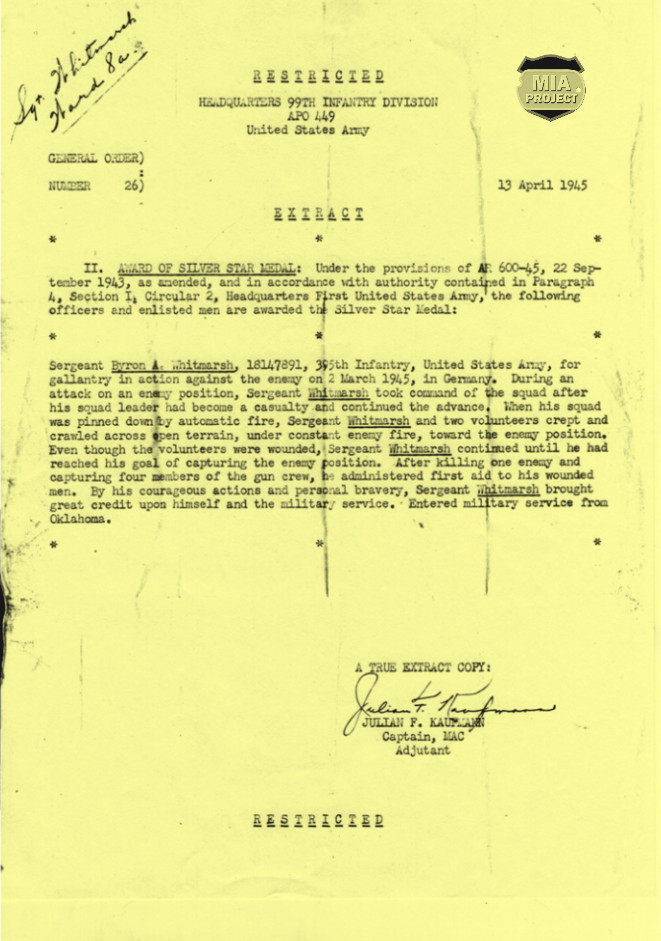

Whit, as he was known in his outfit, went through the hard days of Battle of the Bulge and by March 1945, he was a buck Sergeant and squad leader. The 1st Battalion of the 395th Infantry was approaching the region of Bergheim, Germany, and the resistance was stiff. On March 2, 1945, Company C was about to capture the town of Fortuna and Whit about to earn a Silver Star.

“… I received the Silver Star in the hospital in England in May 1945. The citation is not an accurate description of what really happened. About the only things correct are my name, rank and ASN …” explains Whit with a large smile.

“…Of course in this instance there are the chaos and the disorder of close range firefight but this is the story as I recall it… We had dug in the night before in the woods along a road leading into Fortuna. The Battalion was advancing in a column of two’s with our platoon leading. One column was on each side of the road. We left the woods before daylight, in the fog. Visibility was very limited. The 1st squad was on one side of the road and the 2nd squad was on the other. My squad was split behind the other squads. The squad leaders were leading the squads. Because of the lack of visibility the column moved into a line of Germans dug in along a brick wall. Both sides became aware of each other about the same time and the firing commenced …”

The leading squad leaders were killed immediately and many others in the platoon were hit in the first blast. Everyone hit the ditches and started returning fire. The small arms fire and shouts were deafening, things turned into a wild chaos.

“ … There was a German self-propelled gun to the right of the wall …” continued Witmarsh “… someone got it with a bazooka and the men shot the tankers when they bailed out. The Lieutenant wanted me to take my squad through a shell hole in the brick wall and get in the building … because we were getting heavy fire out of it. A German in a foxhole was between me and the wall. I tried to hit him two or three times when he would bob his head up and down to see what was going on. I decided to try to throw a grenade in his hole twice but missed… While this was going on, Captain Budinsky, the company commander started running down the middle of the road, yelling orders with complete disregard for his safety. He suddently fell forward, he was killed instantly by the flying bullets. He fell not far from me. I asked for another grenade. Someone offered me a white phosphorus grenade and said this would get him even if it didn’t go in the hole. I threw it and it exploded in a much larger radius than I expected and started smoking heavily. When it died down a bit, the Lieutenant said « Go get him now Whit, he can’t see you coming« . I took off but he had gotten away. The way was now clear and I waved to the squad to come on and made it to the wall. When I looked through the hole at the milking stanchions I could see a breath coming up over a curb in front of the stalls so I got another grenade and flipped it over the curb, then we went through the wall. It turned out that had been a pig laying behind the curb, which was now dead. We went into a milkroom but no more Germans. There was a door leading down into a basement. I threw a grenade down the stairs and shut the door. When the blast flung it open, a German came running up the steps with his hands up. He had been knocked goofy from the concussion. I went down the stairs. There was no one left in the small basement but there was an open cellar door leading out to a church and there was a German there. He immediately threw down his rifle and held up his hands. He had a propaganda leaflet which promised safe passage through the American lines and good treatment with a warm dry bed and three hot meals a day. Sounded like a winner. I got the idea that he might cooperate with us and tell us the best way to try to get into the building so I sent someone out to the Lieut. to ask him to send a man who could speak German. His answer was that we weren’t S-2, to send the prisoner out and get the Hell in the building. We found an unlocked window and entered … the Sanctuary to one side of the altar. There was no one in it. To the front, there was a wide corridor between class rooms. We started down the corridor with our rifles ready and came to some stairs leading down. There was some noise coming up the stairs. We pointed our rifles down and waited. A Priest came around carrying a white flag. Behind him were a German Officer and soldiers. He could speak English and said that all the Germans in the building were surrendering. The German soldiers were taken to the vestibule, told to pile up their weapons and sit down with their hands over their heads. The Priest took me down to the big basement. There were wounded soldiers with German medics and a large lunchroom filled with civilians. The Priest was told to tell everyone to stay where they were until the shelling stopped outside. The rest of the platoon, by then only 17 combat ready, came in the building and we began searching to make sure there were no more Germans. Later some tanks came by and we loaded on them and moved on. I never went out and helped the wounded as stated in the citation.

One of the two dog tags Whit carried during the Battle of the Bulge and the day he earned the Silver Star.

A few days later, Company C was sent to attack German positions along the road from St. Katharinen to Steinhardt. The road ran along a high ground and the attack was up a steep slope in heavy woods. « … We were very near the German line all night long … » continued Whitmarsh. We began the attack without artillery during the early morning. Part of C Company was pinned down in a lightly wooded area… We decided to try to get into a house that seemed to line up with the Germans firing into our Company. We only had a short distance of open area to run across to get to a window so we could throw a grenade into the house and get in. The BAR-man was next to me and it was intended that he shoot out the glass in the window before we took off and to cover us. However, I wanted to make sure there were no basement windows at ground level to be used to fire at us. When I raised up to my knees to check this, a German rifleman dug in at the right corner of the house hit me in my upper arm. This hit knocked out about 1 1/2″ of the large bone of the upper right arm and I thought they had shot my arm off because it didn’t hurt at first. I forgot about continuing the war immediately. The shooting commenced by both sides and I crawled down the hill. A medic got to me right away, pulled off the bandage pack from my belt, gave me the sulfa pills, shot me with morphine, bandaged the wound, put on a sling, and offered to get a stretcher. I decided to walk to the aid station with someone to guide me. When Whit arrived at the aid station, the docotor gave him plasma and stopped the bleeding. He then put a wire cage splint on his arm and prepared Whit for the transfer to the clearing station. It wasn’t long before there was an ambulance load ready because casualties were streamin in. « … When in the aid station, shrapnels were banging against the walls outside … » resumed Whit « …the shelling was very heavy. The ambulance was kept in a stall adjoining the building and after leaving the aid station shells landing nearby could be heard most of the way to the clearing station. At the clearing station I was given whole blood and sent on to the Evacuation Hospital right away. The Battalion Surgeon had done a good job getting me ready for the trip. We crossed the river and before long we were beyond the shelling and other sounds of the battle. The realization that our chances of surviving the war had just been greatly enhanced was savored by all those still conscious. At the Evac. Hospital the wound was cleaned out and a cast was put on my arm. The next morning we were loaded into a C-47 and taken to Paris. The next day we were loaded onto another C-47 and taken to a hospital near Blandford, England. At this hospital I was put in traction until the wound healed. With the help of penicillin, this lasted about six weeks. This is where I received my Silver Star…”

Whit’s wound was serious. His major problem was the damage to the nerves in his arm. Unless these could be repaired the arm would be useless. Whit was sent to a hospital near Salisbury, England to be operated on May 11, 1945 and sent to the USA on July 5, 1945. It took a long time for damaged nerves to recover. He arrived at Staten Island and went to Halloran General Hospital for a short time before being shipped to McCloskey Gen Hosp at Temple, TX until January 1946. Then to rehab at Brooks Gen Hosp at San Antonio until March 1946 and then to Kennedy Gen Hosp in Memphis, TN where he was eventually discharged.

“ … The year in the hospitals doing nothing was the longest year of my life…” concluded Whit.

His arm never healed completely and he kept a little handicap. After his discharge, Whit resumed his studies and graduated from Oklahoma A&M in 1948, with a degree in civil engineering. In October of the same year he married Elsie. After working a few years for the Corps of Engineers, he joined a successful general contracting firm until he retired. Whit created a wonderful family retreat at Lake Texoma, where he enjoyed boating, growing tomatoes, and watching grandkids grow and play.

Whit was a member of the 99th Infantry Division Association and attended many conventions. He also made numerous trips back to Belgium and was an active member of the MIA Project. His recollection led to the recovery of missing soldiers of his company.

He passed away on February 12, 2008 at his home in Richardson Texas and was buried at the DFW National Cemetery. He always said that he got a Silver Star for killing a pig.

Souces: Interviews and letters of Byron Whitemarsh.

Items shown on this page were offered by Byron Whitmarsh to the MIA Project Collection.