Liquor ration

Since the dawn of time, alcohol and soldiers have been tightly associated. Alcohol was even considered as a ration in several navies around the globe. The US Navy was the first to abolish the daily rum ration for sailors in 1862. The Royal Navy did the same in 1970 and the Royal New Zealand Navy was the last in 1990!

Successively booty, recompense, morale booster, trade currency or pain killer, alcohol played a major role in wars. WWII was no exception.

Gibson’s whiskey bottle with a 1941 patent recovered on the Elsenborn Ridge. Irish born John Gibson had his distilery established in Pennsylvania.

Gibson’s whiskey bottle with a 1941 patent recovered on the Elsenborn Ridge. Irish born John Gibson had his distilery established in Pennsylvania.

For Allied troops passing through production areas such as Italian or French vineyards or quartered close to big cities, alcohol was a question of opportunity. On their victorious march toward Germany, many GI’s were greeted by locals and the so desired liquid. However, in the damp and misty forests along the German border, alcohol remained a wild dream. On the front line, though, US officers received a monthly allotment of alcohol, known as « liquor ration ». When it reached the front line, it was constituted of four bottles of whatever was available. Scotch whiskey, gin, vermouth, cognac, calvados were among the most frequent but local booze, wine, beer or even champagne were also used to compensate when regular supply was not on hand. Officers used their ration as they would see fit. Some shared it with their men, others didn’t.

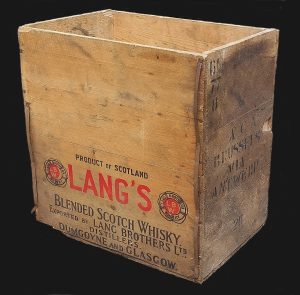

War time wood crate containing 6 two liter bottles of scotch whisky produced by the Lang brothers in Glasgow, Scotland.

In a letter dated December 15, 1944, a few hours before he was killed,

2Lt Lonnie Holloway of Company K, 393rd Infantry, wrote home:

« …We are right on the German-Belgian border at the present. In fact, I have one machine gun in Belgium and one in Germany. Quite an oddity huh! This is a very beautiful country but gee whiz is it cold. There has been snow on the ground continuously since our presence. We (the officers) received a liquor ration the other day. I sort of hated to, but I gave all mine to my men. Well, they deserve it more than I… »

« …We are right on the German-Belgian border at the present. In fact, I have one machine gun in Belgium and one in Germany. Quite an oddity huh! This is a very beautiful country but gee whiz is it cold. There has been snow on the ground continuously since our presence. We (the officers) received a liquor ration the other day. I sort of hated to, but I gave all mine to my men. Well, they deserve it more than I… »

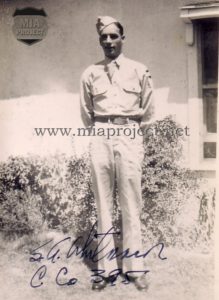

Pfc Byron A. Whitmarsh of Company C, 395th Infantry recalls:

“… When our platoon withdrew from 88 Hill on December 17, the Lieutenant sent me to the command post. It was in a German log bunker we had captured two days before. Captain Budinsky briefed us on the situation as we would be the last of the company to leave. We would be shortly cut off from any road to Krinkelt and everything would be overland by foot. We will have to travel light and leave everything not vital in a rapid retreat. He had just received his liquor ration and didn’t plan to carry a bottle of Scotch. He opened the bottle and passed it around until it was gone. That was the only good thing that happened for some time …”

“… When our platoon withdrew from 88 Hill on December 17, the Lieutenant sent me to the command post. It was in a German log bunker we had captured two days before. Captain Budinsky briefed us on the situation as we would be the last of the company to leave. We would be shortly cut off from any road to Krinkelt and everything would be overland by foot. We will have to travel light and leave everything not vital in a rapid retreat. He had just received his liquor ration and didn’t plan to carry a bottle of Scotch. He opened the bottle and passed it around until it was gone. That was the only good thing that happened for some time …”

A sample of the most frequent bottles recovered on the battlefield (L>R) US 1943 one quart bourbon (whisky) bottle, US 1944 one pint flask, John Dewar & sons scotch whisky bottle (Perth, Scotland), whisky bottle distilled on Islay island (Scotland). The bottles of American origin are all dated and patented, they also bear « Federal law forbits sale or re-use of this bottle »

PFC John Manlich, Jr of Company F, 393rd Infantry, remembers the bottle of gin he carried for his platoon leader:

PFC John Manlich, Jr of Company F, 393rd Infantry, remembers the bottle of gin he carried for his platoon leader:

“… During the Battle of the Elsenborn Ridge, I was runner for the 2nd Platoon. Along with other runners, I was assigned to the company headquarters which were located at the time inside an empty concrete cistern. The floor of the cistern could be reached by climbing down a 20-foot ladder.

One day the platoon commander, by divine luck, received his liquor ration consisting of a bottle of bourbon and a bottle of gin. Much to my surprise, he asked me to take care of them and said he would ask for them as needed. I hid the bottle of bourbon and put the bottle of gin inside my shirt. Because of the heavy shelling, the telephone lines were constantly down. This necessitated carrying the messages and enduring the 88s’ shelling and deep snow. One day as I took my usual prone position in three feet of snow and after hearing the screaming of incoming shells, while lying there in the snow, I felt the bottle of gin inside my shirt. I decided that under the circumstances a sip of gin would feel good and warming. However, after several days and several sips, I suddenly realized that the bottle of gin was almost empty and the lieutenant might soon be asking for the return of his ration. In order to delay the discovery of my transgression, I filled the bottle with snow so the casual observer couldn’t tell the difference between melted snow and gin.

Almost on cue, the lieutenant called for his bottles. With great fear and concern, I gave him back his rations. At this point my imagination took hold and I imagined all sorts of punishments –from a tongue lashing to a court-martial or being shot by a firing squad. While contemplating my fate, my buddy came running up to me and said the lieutenant was climbing down the ladder in the cistern with the bottle of gin in his hand. It slipped from his grasp, fell to the concrete floor, and broke into what appeared to be a thousand pieces! I felt there must have been divine intervention to save me from my just punishment …”

Several former 99th division officers have no recollections of a liquor ration being received. US Army officers had a particular overseas status and had to pay for some of their supplies, such as uniforms or food. It was thought that the liquor ration was optional and that they had to pay for it.

1st Lieutenant Samuel L. Lombardo, platoon leader in Company I, 394th Infantry.

« …We had a ration of four bottles a month. I don’t remember paying anything for it. At the time on the Elsenborn Ridge, I did not drink so I gave all of it to my NCO’s and they shared with the men in the platoon. It was an automatic receipt every month and we had no choice as to what we received but I remember it was plain bourbon and vodka. I wish that it had been wine and I would have drunk it… »

« …We had a ration of four bottles a month. I don’t remember paying anything for it. At the time on the Elsenborn Ridge, I did not drink so I gave all of it to my NCO’s and they shared with the men in the platoon. It was an automatic receipt every month and we had no choice as to what we received but I remember it was plain bourbon and vodka. I wish that it had been wine and I would have drunk it… »

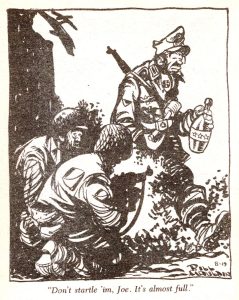

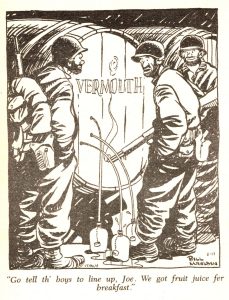

American servicemen in World War II had to work hard to find booze. For those serving overseas, access to liquor, other than in big cities, was extremely limited. On the front, they drink whatever they could find, liberated or were offered during their victorious advance. Cartoonist Bill Mauldin, himself a combat infantryman, perfectly described this constant quest for the precious liquid through his famous characters Willie and Joe.

Many GI’s however received booze in packages from home, especially at Christmas. Though prohibited by the Army, alcohol often reached the front in a fake pots of jam or a flasks hidden in empty cakes.

S/Sgt Richard H. Byers, of Battery C, 371st Field Artillery Battalion :

“… By Christmas Eve, we were really feeling low down and depressed … we were on the second floor of a farmhouse … downstairs were 8-10 children … singing Christmas carols. We were about to go to bed when someone yelled “Mail Call!” and there was our Christmas mail. I received two boxes from my wife and in each was a can of candy corn. In each can was a two ounce medicine bottle filled with good wiskey. I gave the candy corn to the kids downstairs and shared the fruit cake with the boys but I let each one have a little taste of the wiskey…”

“… By Christmas Eve, we were really feeling low down and depressed … we were on the second floor of a farmhouse … downstairs were 8-10 children … singing Christmas carols. We were about to go to bed when someone yelled “Mail Call!” and there was our Christmas mail. I received two boxes from my wife and in each was a can of candy corn. In each can was a two ounce medicine bottle filled with good wiskey. I gave the candy corn to the kids downstairs and shared the fruit cake with the boys but I let each one have a little taste of the wiskey…”

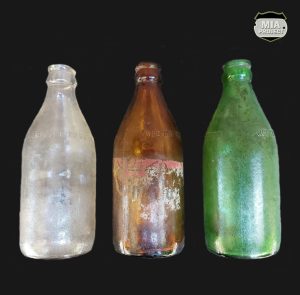

On the front, empty alcohol bottles often landed in the dugout’s garbage pit. Some found a second use. Even when the day was bright and clear, light never penetrated inside a log covered dugout, darkness was the constant companion of the dogface. He used every trick to make light to write home, eat, read, play cards, clean his weapons or simply shave. Some burned the cardboard from K rations boxes, others made trench lantern out of a can or a bottle. Of particular interest is this scotch bottle containing a sock. Filled with gasoline, with the sock as a wick, the bottle became an improvised lantern. Probably giving only a thin and shaking flame, lots of soot but providing enough light to write home or talk with a foxhole buddy.

On the front, empty alcohol bottles often landed in the dugout’s garbage pit. Some found a second use. Even when the day was bright and clear, light never penetrated inside a log covered dugout, darkness was the constant companion of the dogface. He used every trick to make light to write home, eat, read, play cards, clean his weapons or simply shave. Some burned the cardboard from K rations boxes, others made trench lantern out of a can or a bottle. Of particular interest is this scotch bottle containing a sock. Filled with gasoline, with the sock as a wick, the bottle became an improvised lantern. Probably giving only a thin and shaking flame, lots of soot but providing enough light to write home or talk with a foxhole buddy.

Cold beer

When mobilization started for World War II, many prohibitionists wished to ban all alcohol from military bases. The Army however had other intentions and opened USO and service clubs where servicemen could find music, good company and … cold beer. Commanders knew that serving beer would keep their men on base and away from the local bootleg booze and prostitution. Beer was rooted in the American traditions since the frontier days and the first immigrants. The taste for lager beer became the genuine preference rather than the bitter British style ale. Beyond the taste, lager beer was traveling better and had longer preservation than ale. It became army standard. The government signed contracts with large US breweries asking them to set aside 15% of their production for military use and with a 3,2% of alcohol instead of the usual 4 to 7%. This new need for million scale of 3.2 percent beer revived the breweries that survived prohibition.

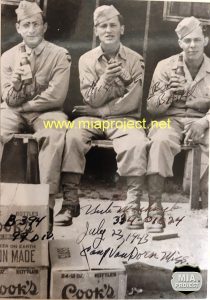

Cpl Nick Machnick (center) is celebrating his 22nd anniversarry with platoon friends, including Cpl Robert J. Baird (right) and Pvt Phieffer (left). The men belonged to Co B of the 394th Infantry.

The birthday party is largely supplied with Indiana brewed Cook beers.

For troops deployed overseas, the Army provided beer for military camps, recreation centers and through the Post Exchange system (PX), but the precious beverage seldom reached the front lines.

Three variations of Rheingold lager beer bottles recovered in positions occupied by the 99th Division. According to the law, they are all marked « Not to be refilled – Not deposit no return »

In Italy, France or Belgium , there are hundreds of stories involving US servicemen using army goods as trade currency for booze. Among those stories, there is one involving Marcel Compere, a Belgian farmer living a couple of miles west of the town of Spa, headquarters the 1st US Army. By a warm afternoon of early october 1944, a US army 6×6 truck stopped in front of Marcel’s farm with obvious mechanical issues. Despite the language barrier, Marcel tried to help the American truck driver to repair his truck but to no avail. Both men finally ended up having a drink and fraternizing. The truck driver then offered his diasabled truck for a bottle of Marcel’s booze. Deal! Both men were entirely satisfied. The truck was pushed in the barn and the truck driver went back to Spa on foot. The next morning, an MP jeep and a prime mover stopped at Marcel’s farm. The truck driver, handcuffed, was sitting on the back seat of the MP jeep. The truck was quickly removed from the barn and towed back to Spa, leaving Marcel without his precious deal and rid of a bottle of his private booze reserve!

Over the last four decades of research on the battlefield, the MIA Project members recovered quite a few bottles of alcohol of different brands, colors and origins, as well as bottles of beer. This page is a sample of our recoveries.

Sources:

MIA project collections

Interviews and letters from Richard H. Byers, Samuel Lombardo, Byron A. Whitmarsh.

Letters from John Manlich, L.O.Holloway.

Web information.