Krinkelt Forest – December 17, 1944 – 13:00 hours

Nineteen-year-old New Jersey resident James Larkey quickened his pace. The noise of distant machine-gun fire and grinding tank tracks followed his platoon from Company I, 394th Infantry, as it crossed Jans Creek. Carefully avoiding the main trail, the retreating men moved uphill and came upon a defensive line established by the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Infantry. Larkey paused to catch his breath.

Company I, 394th had been busy over the last few days. As the only 99th Division reserve, the company had been temporarily attached to the 395th RCT on December 13 for an attack on the Siegfried Line. Late on the 16th, they had hurried three miles south to support Lt Col Jack Allen’s 3rd Battalion, 393rd Infantry in the Krinkelt Forest. Their orders were simple: help Allen’s badly shaken battalion restore its lines after a strong German attack that day. Unknown to them, the German attack was a massive offensive along the entire Ardennes front.

With the first light on December 17th, tanks from the 12th SS Panzer Division supported by swarms of SS grenadiers attacked Allen’s depleted battalion in the forest. Under that unbearable pressure, Allen was ordered to withdraw toward Krinkelt through Lt Col Paul V. Tuttle’s 3rd Battalion, 23rd Infantry from the 2nd Infantry Division. Tuttle’s men held positions half a mile to the west and would back up the withdrawal.

The men encountered by Larkey and his platoon were from Captain Charles B. MacDonald’s Company I, 23rd Infantry, 2nd Division. They had arrived during the night and deployed to cover the withdrawal. They had instructions to hold at all costs, allowing time for the 2nd and 99th Divisions to organize a defense around the twin villages of Krinkelt and Rocherath. MacDonald’s men knew what was coming and had only enough ammunition for a brief fight.

Larkey remembered, “The guys seemed very calm, and we gave them our bandoleers.” He and his companions emptied their pockets, giving hand grenades and extra M1-rifle clips. He talked briefly with a 2nd Division Sergeant and left.

Not long afterward, MacDonald’s company battled the SS men and machines for nearly two hours before being overrun and almost annihilated. Tuttle’s battalion later received two Medals of Honor and a Presidential Unit Citation. MacDonald eventually became a noted military historian, and his experiences in the forest became two chapters in his classic memoir, Company Commander.

When Seel and Speder discovered this area in 1980, it was almost untouched. All sorts of equipment laid on the ground. In a foxhole line overlooking Jans Creek, the Belgians discovered traces of a hot firefight. One shallow entrenchment adjacent to the main trail attracted their attention. Dozens of spent M1 rifle cartridges surfaced in and out the foxhole. All of a sudden, among the corroded cartridge cases, a shiny object appeared—a stainless steel dog tag reading, “Neely W. Wyatt”.

When Seel and Speder discovered this area in 1980, it was almost untouched. All sorts of equipment laid on the ground. In a foxhole line overlooking Jans Creek, the Belgians discovered traces of a hot firefight. One shallow entrenchment adjacent to the main trail attracted their attention. Dozens of spent M1 rifle cartridges surfaced in and out the foxhole. All of a sudden, among the corroded cartridge cases, a shiny object appeared—a stainless steel dog tag reading, “Neely W. Wyatt”.

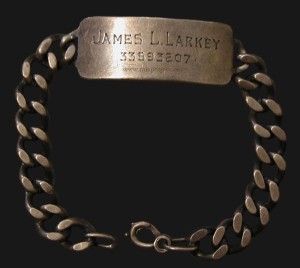

On the opposite side of the foxhole, Seel unearthed a large sterling silver ID bracelet engraved “James L. Larkey.” The men had seemingly shared the same foxhole and were involved in the shooting.

The truth proved different.

Neely W. Wy att, a staff sergeant with Company I, 23rd Infantry, had not survived the war. The twenty-seven-year-old auto mechanic from El Paso, Texas, died on December 18 according to official records. That date probably is wrong. He likely perished the day before, just after meeting Larkey. Incorrect dates of death are common and often resulted from the mayhem generated by the battle. Large groups of men were reported missing in action on the same date without regard to individual circumstances. This practice was expedient from an administrative perspective. Wyatt’s name appeared on a company morning report dated December 29, and the reported list he and his comrades missing on the 18th. He is buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery, El Paso, Texas, Plot E, Grave 9486.

att, a staff sergeant with Company I, 23rd Infantry, had not survived the war. The twenty-seven-year-old auto mechanic from El Paso, Texas, died on December 18 according to official records. That date probably is wrong. He likely perished the day before, just after meeting Larkey. Incorrect dates of death are common and often resulted from the mayhem generated by the battle. Large groups of men were reported missing in action on the same date without regard to individual circumstances. This practice was expedient from an administrative perspective. Wyatt’s name appeared on a company morning report dated December 29, and the reported list he and his comrades missing on the 18th. He is buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery, El Paso, Texas, Plot E, Grave 9486.

Jim Larkey was born on January 31, 1925, in Red Banks, New Jersey. He joined the ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program) at John Tarleton Agricultural College in Stephensville, Texas. When the program was disbanded early 1944, he joined company I, 394th Infantry, as a basic infantryman. He made his way through the war with the same unit. Upon returning home, he finished his college studies and worked at the family owned chain of men’s wear stores. He joined the 99th Division Association and attended many reunions. When the story of bracelet reached him, Larkey couldn’t believe it.

“…When I was inducted in the army, my mother bought me a silver ID bracelet engraved with my name and ASN. I wore it all through the first 18 months. After we went onto the attack in the Ardennes, my outfit was transferred to the 393rd Infantry sector. … We were forced into a chaotic withdrawal, and this is where I apparently lost the bracelet…”

Larkey agreed to leave the bracelet in Seel’s collection. But in 2008, Jim asked Seel if he could have the bracelet for his family and future generations.

“…I can’t help speculating that if it had stayed in my possession for 68 years, I might have misplaced or otherwise lost possession. But, because it was in Belgium all those years, acquiring the glamour of the circumstances, it now is an item of interest for my grandson and future family members…”

Seel graciously agreed and returned the bracelet. James Larkey passed away on November 14, 2012, at Longwood, Florida. He was eighty-seven.

Jim Larkey (left) is pictured with his brother Lewis, a lieutenant in an antiaircraft unit attached to the 2nd Infantry Division (note the liberated German infantry assault badge on Lewis’s belt). The brothers met several times during the war and sent this photo to their mother. Jim and Lewis first met before the Battle of the Bulge when Jim’s outfit was still in the forest. Lewis found the company CP and the CO sent for Jim. As Jim approached, he walked right past his brother without recognizing him. The two had a good laugh.

“My mother ...” added Jim, “… hadn’t heard from me in six weeks and notified Lewis. She asked him to find me. Lewis sent a copy of the photo. I thought we looked wonderful, but my mother was distraught about how awful we appeared.”

Sources:

Conversations and correspondence with Jim Larkey.