By JP Speder

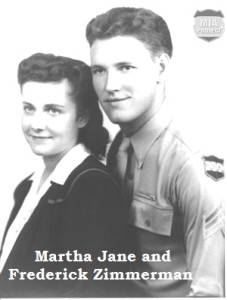

Sgt Frederick F. Zimmerman

Sgt Frederick F. Zimmerman

Co H/394th Infantry – Groveport, OH

PFC Ewing E. Fidler

Co E/394th Infantry – Ada, OK

PFC Stanley Larson

Co H/394th Infantry – Rochelle, IL

I. Historical background

In early December 1944, the 394th Infantry had two battalions on line, the 1st and 2nd. Both battalions held positions in a heavily forested area along the Belgian-German border. The 1st Battalion was at the edge of the forest overlooking the German town of Losheim, and the 2nd Battalion lay immediately to the north. The 3rd Battalion was in reserve at Buchholz, a hamlet just behind the 1st Battalion.

The 2nd Battalion was dug in along a main road nicknamed “California road.” That road ran north-south along the border and is today Highway 265. The companies on line were Company E on the left flank and overlooking the villages of Neuhof and Udenbreth, then Company F in the center, and finally Company G on the right flank. Companies F and G were entrenched in a thick spruce forest. The front line ran almost parallel to the German side of California road. This meant that large portions of the road were under German observation and could not be used by vehicles. The MSR (Main Supply Road) for the 2nd Battalion was a dirt trail coming from Mürringen, Belgium, and running into the forest up to California road. That dirt trail, having been used countless times by other outfits, had been covered with logs and was known as “Corduroy road.”

On the morning of December 16, 1944, the Germans unleashed a tremendous artillery barrage that lasted about an hour. Though badly shaken, the battalion suffered little damage. Communications were poor, and the situation in other sectors was confused. The next day, December 17, conditions had worsened on the regimental front, and the 2nd Battalion received orders to withdraw to Mürringen. The order came by runner at 14:05 and stated the retreat would begin at 15:00. Captain Ben Legare, then leading the battalion, summoned his company commanders and issued march orders. The troops were to abandon anything that could not be carried out.

II. MIA search along California Road

When the MIA Project began in 1990, Rex Whitehead, a Company H veteran, championed three 2nd Battalion casualty cases: Sgt Zimmerman and PFC Larson, both from the same Company H heavy machine gun platoon, and PFC Fidler of Company E. Whitehead spearheaded research efforts. He gathered eyewitness reports indicating that the three soldiers died during the German artillery barrage on the morning of December 16, and the body of at least one was last seen at a forward aid station.

From W.B. Williams, Company H veteran:

“Fred [Zimmerman] was squad leader and I first gunner on a water-cooled .30 cal. We were two men short, so we were on gun duty for extremely long hours. Fred and I went on gun duty at 0200 on Dec 16, and everybody knows about the artillery barrage that hit us at 0515. Our gun pit for the heavy 30 was not really deep, but the logs kept us from harm for 40-45 minutes. Apparently a shell hit behind us and the blast came in our direction. I was hit in the right arm and Fred was caught in the right side. Before I could react, he jumped up and started running toward the aid station. The shelling finally stopped, and 10-15 minutes later medics began searching the area. I heard one say these terrible words: Here’s one. He’s dead. This was Fred.”

From Andrew Woods, Company H veteran:

“I was with

Larson in the hole that morning and he caught most of the force of the shell which saved my own life. One of my legs was shot up and broken and both hands damaged. Larson’s gut was all torn up and his legs were almost gone. … Medics got me out of the hole and carried me to the aid station.”

From Warren Wenner, Company H veteran:

“I helped carry Larson to the aid station. … One leg was barely attached and almost hanging on with skin. … We just put the litter down and left.”

From Angelo Spinato, Company E veteran:

“I remember Fidler vividly. I can still picture his body just outside the E Co CP. He was killed in his bunk by a shell that penetrated the cabin, exploded, killing him and seriously wounding the 3rd Platoon leader. His name escapes me at this time. When we pulled out, Fidler was left there.”

From Gray Smeltzer, 394th Medical Detachment veteran:

“When we left the forward aid station to join our unit in the withdrawal, there were 10 or 12 bodies left there in mattress covers. Zimmerman’s body was there, but can’t be positive about Larson’s. Since a general withdrawal was in process it’s doubtful they were removed by our men.”

Gray Smeltzer drew a sketch to help locate the forward aid station, but the sketch was too imprecise to lead our search team to the spot. Time drifted by and repeated search efforts yielded nothing.

III. Recovery operation

On May 25, 2001, Marc Marique began a new search for the forward aid station. He followed Smeltzer’s map and eventually reached a place discovered many years before. Marique unearthed rusty nails, broken shingles, and, near a large dugout, several empty morphine syrettes. Among the syrettes a dog tag surfaced: Frederick F. Zimmerman. Had the aid station been discovered? On June 1, Marique, accompanied by Jean-Louis Seel and Jean-Philippe Speder, returned to the site. Since there were only four or five dugouts, the group decided to empty them one at a time. To empty a hole means removing the dirt and slash accumulated over a half century to reach the original soil layer. The first two holes contained nothing of importance. Marique began the third one and soon unearthed a snow boot. The dirt around the boot was carefully removed, and a tibia appeared. Marique had found Zimmerman. But that was only the beginning. Two more bodies emerged in the same hole. The other two were Fidler and Larson.

On June 1, Marique, accompanied by Jean-Louis Seel and Jean-Philippe Speder, returned to the site. Since there were only four or five dugouts, the group decided to empty them one at a time. To empty a hole means removing the dirt and slash accumulated over a half century to reach the original soil layer. The first two holes contained nothing of importance. Marique began the third one and soon unearthed a snow boot. The dirt around the boot was carefully removed, and a tibia appeared. Marique had found Zimmerman. But that was only the beginning. Two more bodies emerged in the same hole. The other two were Fidler and Larson.

As the Belgians carefully removed human remains and personal belongings from the common grave, a red fountain pen appeared in the uniform shreds of Stanley Larson. To the complete astonishment of the group, a name was engraved on the pen: “Rex Whitehead.”

Whitehead and Larson had been good friends, and that friendship had spurred Whitehead to join the MIA Project. The last time he had seen Larson was on a vessel that carried them across the English Channel. This is perhaps when the pen arrived in Larson’s possession.

Forest ranger Erich Hönen was notified and soon joined the three diggers. Jean-Luc Menestrey, the fourth member of the team, joined, too. Zimmerman and Fidler were removed that same day and transported to the ranger’s home. The team met again the next day to remove Larson and prepare all the remains for the U.S. Army Memorial Affairs Activity-Europe.

On June 05, 2001, David B. Roath, Memorial Affairs Director, arrived to inspect the remains and organize an official site clearance. It took place the following week. The 21st Theater Support Command at Landstuhl, Germany, dispatched a six-man team which worked three days on site. Also, administrative details had to be ironed out with the local authorities because the remains were recovered in Belgium. To wrap up the process, Roath suggested that a fallen soldier ceremony be conducted at the nearby church in Krinkelt. The ceremony took place on June 29, 2001.

IV. Fallen Soldier Ceremony

The small stone church was crowded that day. The local mayor, Gerhard Palm, welcomed special guests including U.S. Ambassador Steven Brauer. An honor guard from the U.S. 1st Infantry Division was present as was a Belgian Army honor guard. After ambassador’s speech, the Belgian soldiers marched away, and the American soldiers replaced the Belgians. They carried three flag covered transfer cases outside to waiting hearses. Two buglers rendered “Taps,” and the vehicles pulled away escorted by Belgian Army military police.

At Landstuhl, Germany, Roath’s team prepared reports and coordinated transfer of the remains to the Central Identification Laboratory-Hawaii. There, forensic anthropologists and odontologists examined the remains in an effort to establish positive identification.

Years before the recovery, the MIA Project had established contact with the families of the soldiers. They were made aware of recent events. U.S. Congressman Mark S. Kirk and his representative Roy Czajkowski provided oversight to ensure the identification process progressed in a timely manner. The process took only six months which was unusually fast for an organization that normally took more than a year to complete such identifications.

Immediately after the war, President Truman signed legislation giving families the option of bringing their dead loved ones home or leaving them overseas in permanent U.S. military cemeteries. That option was still available in December 2001 when CILHI confirmed the identities of the three servicemen.

IV. Final Journey

Chuck Fidler, brother of Ewing Fidler, decided to bring his brother back to Rosedale Cemetery in Ada, Oklahoma, where his family had a plot. Ewing was buried beside his Mom and Dad on Saturday, June 8, 2002.

Stanley Larson also came back to his hometown. Leon, his older brother, selected the family plot as final resting place. The funeral occurred on July 22, 2002. Seel and Speder joined their American teammates at the United Methodist Church in Rochelle, Illinois. For Rex Whitehead it was the end of a long quest. His friend was finally home. He had made plans to attend the funeral, but poor health precluded a trip to Illinois. He wrote a eulogy and was represented by his older daughter Robyn and her husband Ron. After the service, the pastor led the crowd to the Lawnridge Cemetery where soldiers from Fort Leonard Wood conducted the graveside service.

Six weeks before the recovery along California road, the MIA Project had recovered three missing soldiers from the 395th Infantry (see » 88 Hill »). The close timeframe of the recoveries led to an unusual funeral arrangement. Two of the 395th families had decided to inter their loved ones at the American military cemetery located near Henri Chapelle, Belgium. Bill Zimmerman decided that his brother’s resting place should be there, too. It would be the first burial at Henri-Chapelle since 1954.

As a licensed funeral director, David Roath retuned to Belgium to orchestrate the funeral. Single funerals were rare at American cemeteries, so a triple funeral would undoubtedly generate broad interest.

On June 22, 2002, more than one thousand Belgians citizens and local patriotic associations gathered at Aubel’s Saint Hubert church to greet the funeral cortege. After the ceremony, part of the crowd accompanied the families and the fallen soldiers to the cemetery where a U.S. Army honor guard carried the flagged caskets to shiny catafalques. The chaplain conducted a moving ceremony. The pall bearers folded the flags, and an officer presented them to the families.

One final ritual concluded the ceremony. The families shoveled a few lumps of earth into each open grave, as did David Roath and the MIA Project members. The funeral party vacated the cemetery, leaving Roath’s crew to cap the burial vault and backfill the soil.

Days later, Seel, Speder, and Bill Warnock escorted the Zimmerman family to the recovery site.

Frederick Zimmerman, like his unfortunate companions, had finally found a resting place befitting with the measure of his sacrifice.

Sources:

Ewing Fidler, Frederick Zimmerman & Stanley Larson– IDPF’s

After Action Report – 2st Bn, 394th Infantry.

Interviews and correspondance with Rex Whitehead, Grey Smeltzer, Warren Wenner, Andy Woods, W B Williams & Angelo Spinato

Photos courtesy Chuck Fidler, Bill Zimmerman and Larson family

MIA Project data collection.